The Practice of Confidence

Confidence is built more than it is felt.

Clients in leadership coaching and communications trainings often share a common goal: to increase their feelings of confidence, especially in high-stakes meetings and conversations.

Here's the counterintuitive truth, and one of the most liberating insights about confidence: confidence is built more than it is felt.

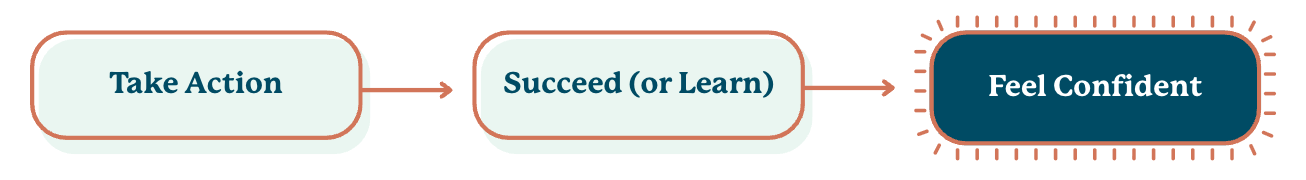

It grows as a result of trial and error and experience over time, versus being the result of genetic luck. Most of us think the sequence goes: feel confident → take action → succeed.

But it actually works in reverse: take action → succeed (or learn) → feel confident.

Confidence comes after action, not before.

When we wait to "feel ready" before speaking up or acting on what we really want, we're waiting for a feeling that only comes after we've taken the action. Think of it like physical fitness. You don't wait to feel fit before going to the gym. You get fit by going to the gym—through those first awkward workouts, the muscle soreness, the gradual building of strength over time.

Confidence works the same way.

It’s not always comfortable or easy, but there is a path that supports the kind of evolution we want. Every time we move through discomfort and act anyway, we're creating evidence that counters our reluctance and fear. "I felt anxious, I did it anyway, and I survived—even thrived."

What supports an ongoing practice of confidence-building?

There are many ways to incorporate practice into our daily work and life routines. Here are a few.

Solicit feedback.

Trusted friends and colleagues are excellent allies when it comes to sharpening our skills. If we’re worried about how we appear in certain settings, wouldn’t we want to know what others might offer us in terms of guidance and support? If expressing an increase in confidence is a goal, we’d do well to figure out what we’re currently doing (or not doing) to advance that objective.

A new CEO once asked me for feedback after watching him address a large audience during an annual event. He was working on projecting steady and confident leadership as he took on his new role. This gathering offered an ideal opportunity to do so.

As I watched, it was clear that his nervousness betrayed him in the form of a near constant smile. His speech was a key opportunity to project gravitas in a high-stakes moment, to signal command of the room and the content being delivered. But his body language was inadvertently signaling “too nice” and “too green,” diminishing his very passionate and well-prepared remarks. What was skillful in certain situations, a friendly smile, revealed itself instead as a tell.

He was grateful to hear this assessment - it made sense. He’d long received comments about his affable nature; sometimes an asset, sometimes a liability. This event gave him the chance to ask for specific feedback on his leadership presence, and he was wise enough to take it. As a result, he learned more about how and when to let his warm and personable nature work for him, rather than against him.

Ask questions.

Many of us fear asking questions when we don’t know something. The emotional risk of looking foolish can override the benefits of learning something new or getting help. The good news is that we don’t have to work hard to surface questions when faced with uncertainty. We just need the courage to speak them aloud. Questions are an excellent way to nudge ourselves through uncomfortable territory.

In my first year as an executive director, I came by several lessons the hard way when reporting to the board. I desperately wanted to appear confident and capable, but my imposter syndrome was running the show. What undermined me was the assumption that I had to have the just-right response to questions and challenges. Trying to appear calm under pressure only drained much-needed mental energy, wasting it on looking in charge rather than being in charge.

A shift came as I began to ask more and answer less when feeling uncertain. Instead of giving long-winded responses when caught off guard, I gathered the confidence to be curious. What about that concerns you? Say more about how you came to that conclusion. What would change your mind? How does your idea support our stated goals?

Asking questions didn't just buy me time—they made me a better leader.

I learned this through hard experience, continued education, and eventually by coaching others through the same struggles. The only way to know if my advice was good was to keep following it myself. So far, it's working—and I'm still learning to let go of control and perfectionism in real time.

Continue to grow and learn.

There are workshops, courses, coaches, mentors, and numerous other resources waiting to support us. Deepening the skills and mindsets that support clarity and self-assurance is always worth the investment.

When I host leadership communication trainings, the most confident participants sometimes struggle the most. They arrive as self-identified (and other-identified) skilled speakers, expecting to add a few tools to an already robust toolkit. They often appear relaxed at the start.

Then the front-of-room exercises begin. They stumble more than anticipated. Many become visibly flustered - not by the difficulty itself, but by the gap between their self-perception and their performance in the moment. The fixed mindset kicks in: "I'm already good at this. I shouldn't be struggling. This is bad." When our self-image feels challenged, our confidence can take a serious hit.

But by the end, these same participants often express the deepest appreciation. They discover that new strategies can make them even more impactful than they already are. The initial discomfort becomes the doorway to growth. Confidence and competence aren't fixed states. Even the most skilled among us have blind spots, room to evolve, and new layers to explore. Sometimes the people who think they need it least benefit the most.

Building a practice by building the evidence

For all of us, confidence comes from accumulating evidence of our ability to handle uncertainty, to cope, to learn, to bounce back. People who appear most confident often experience intense nerves and anxiety; they've just learned that those feelings don’t have to stop them.

Confidence doesn't come from the absence of fear or doubt. It comes from moving forward with them, by inviting them into our practice, not by waiting for them to disappear.

What's something you've been waiting to feel ready for?

FAQ

-

There's no shortcut, but the fastest path is to start taking action immediately in areas where you want to feel more confident. Each time you act despite discomfort—whether it's speaking up in a meeting, asking a question, or trying something new—you create evidence of your capability. Confidence accelerates when you combine action with feedback and reflection on what you're learning.

-

DescrAct despite the nervousness rather than waiting for it to pass. Start small: ask a single question in a meeting, or share one observation. Each time you speak up while anxious and survive the experience, you build evidence that the fear was manageable. The nervousness doesn't need to disappear before you act—confident people have simply learned this truth.

-

Absolutely. Even highly skilled people have blind spots and room to evolve. In fact, experienced professionals sometimes struggle most when facing new challenges because their self-image clashes with their performance in unfamiliar territory. A growth mindset—believing you can develop further regardless of current skill level—is essential for sustained confidence. The most impactful leaders remain students of their craft.

-

Confidence doesn't come from preparation alone—it comes from accumulating evidence of your ability to handle uncertainty through repeated experience. The sequence isn't feel confident → act → succeed, but rather: act → succeed or learn → feel confident. Waiting to "feel ready" means waiting for a feeling that only arrives after you've taken action.

-

Three key practices build workplace confidence: (1) Solicit specific feedback from trusted colleagues about your performance in high-stakes situations, (2) Ask questions when uncertain rather than pretending to have all the answers, and (3) Invest in ongoing learning through workshops, coaching, or mentorship. Each practice helps you gather evidence of your capabilities over time.

-

Confident leaders don't lack fear or nervousness—they've simply learned that these feelings don't have to stop them from taking action. They move forward with anxiety rather than waiting for it to disappear. The difference between confident and hesitant leaders isn't the absence of doubt, but the willingness to act despite it.

-

Focus on eliminating nervous tells that undermine your message. Common tells include excessive smiling during serious content, fidgeting, or rushing through material. Solicit specific feedback from trusted colleagues about your body language and delivery. Ask them: "What signals confidence? What undermines it?" Then practice incorporating their guidance. Remember that projecting confidence comes from genuine engagement with your content, not from performing calmness.